.I found this piece in "Introduction to Don Quixote", 1986, by E.C. Riley. Unfortunately my copy is in Castilian so this is my translation from the Spanish transition. Apologies to the author. The period was characterised by a timid awakening of the scientific method coexisting with medieval forms of investigation, or a confusion of empirical fact and poetic myth. Quijote excerpts are from John Ormsby translation. (Epistemology: the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature, origin and scope of knowledge)

"Particularly deserving of attention in the novel are two passages which together clearly illustrate two interconnected circumstances, of prime importance in the intellectual history of the period, an importance which in the latter case has not faded in the slightest over time. Both are related to myth, authority and experience.

The first circumstance is a question of epistemology. Possibly the greatest development in the methodology of intellectual investigation around 1600 was the gradual passing from authority, as a fundamental source of veritable truth, to observation, experimentation and induction, methods on which the new sciences and the philosophy of Kepler, Bacon, Galileo and Descartes were based. In reality, we could study the dichotomy "experience" versus "authority" as a general theme in the Quixote. But a passage in the second part, chapter 1, properly concentrates (?) the question.

" With regard to giants," replied Don Quixote, "opinions differ as to whether there ever were any or not in the world; but the Holy Scripture, which cannot err by a jot from the truth, shows us that there were, when it gives us the history of that big Philistine, Goliath, who was seven cubits and a half in height, which is a huge size. Likewise, in the island of Sicily , there have been found leg-bones and arm-bones so large that their size makes it plain that their owners were giants, and as tall as great towers; geometry puts this fact beyond a doubt."

Therefore, giants have existed, a) because the decisive accepted authority, the truth revealed in the Bible, says so; and b) because its existence has been empirically proven by a process of scientific induction. Each method serves as a support for the other in order to demonstrate here the validity of this opinion. The passage vividly illustrates the curious coexistence during this period of two approaches to knowledge which from the modern point of view are almost incompatible. Taking into account who is speaking and the topic of conversation, it is possible that Cervantes was being ironic about their connection here, but it is not in the slightest certain that he was even aware of the existence of an incongruence.

The second example concerns myth and experience, as much as authority and experience. When Don Quijote announced for the first time his intention of exploring the wonders of the Caves of Montesinos, he gives us as an additional reason his to explain his intention of searching there for the source and the origin of the nearby Lagunas de Ruidera and the River Guadiana, which flows in part underground.

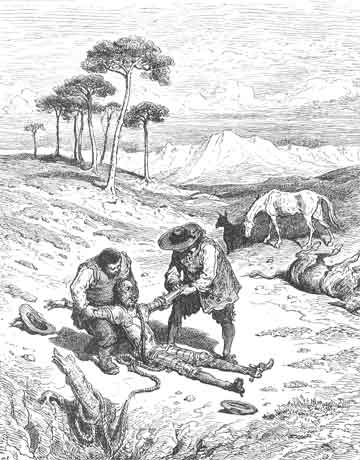

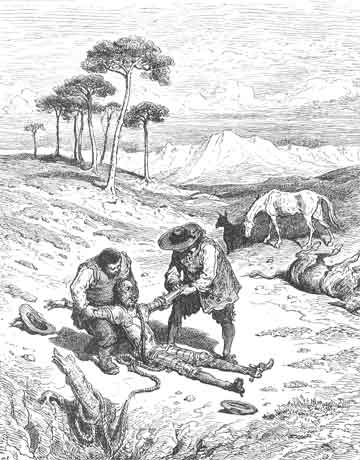

Don Quixote around the Caves of Montesinos by French illustrator Gustavo Doré (1833-1883)

" first of all, he meant to enter the cave of Montesinos, of which so many marvellous things were reported all through the country, and at the same time to investigate and explore the origin and true source of the seven lakes commonly called the lakes of Ruidera".

This is clearly a question of exploration, that is, an empirical investigation, but when he later relates his experience in the cave, he answers the problem of the place of origin of these waters in very different terms. Montesinos had told him that the lakes were once Doña Ruidera and her seven daughters and two nieces, and the River Guadiana, the squire of Durandarte. They wept so much for the death of Durandarte that Merlin transformed them into (ten) lakes and a river. The sadness of the river Guadiana is so evident is, says Montesinos, that it submerges underground at different points, and also the fish in the river are of very poor quality. It seems that Don Quijote is satisfied. A simple question of geographical or geological investigation becomes a pure myth (and it is a magnificent piece in the construction of a myth), sustained by the authority of Montesinos, a hero invented from the popular 'Carolingian' romances.

|